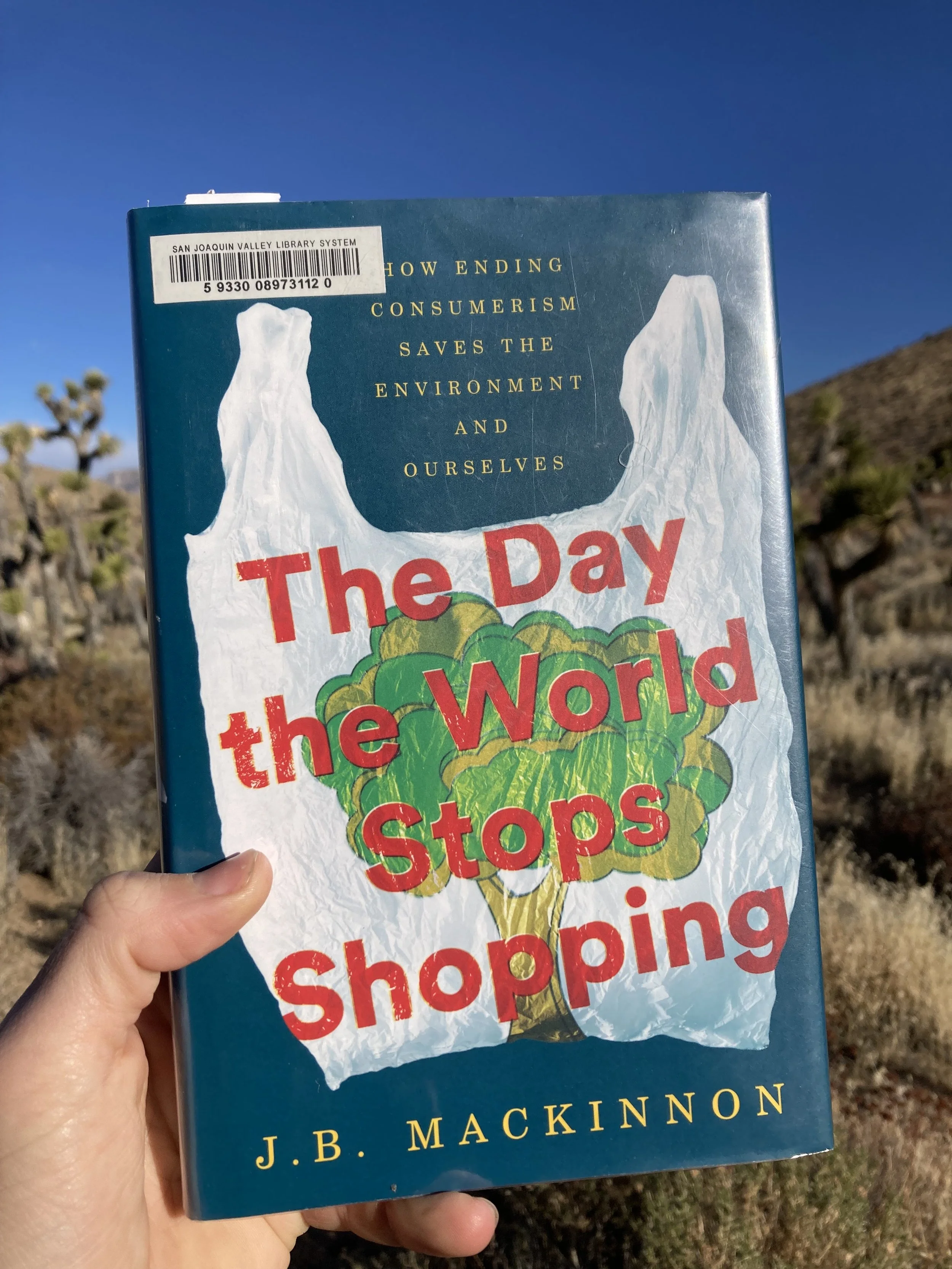

I read The Day the World Stops Shopping: How Ending Consumerism Saves the Environment and Ourselves by J.B. MacKinnon.

I expected it to be a bit of a yawn for me because at this point I consider myself an established member of the anti-consumer choir and I assumed it’d be a light green treatment of consumerism of the ‘change your lightbulbs’ variety, but I was wrong. The book was fascinating.

The 'what would happen if the world stopped shopping?’ thought experiment worked nicely to make the big picture ideas grounded, I learned a lot of interesting historical context I didn’t know, and he walked through thinking about life in our society from angles that churned up fresh insights for me (I’ll do anything for fresh insights).

As a teaser, MacKinnon’s section on the development of GDP blew my mind. The guy who invented the accounting methods of GDP was himself a critic of overemphasis on GDP. From the book (bolding mine):

Near the end of the Great Depression, a Russian Jewish immigrant and brillilant economist named Simon Kuznedts developed America’s first national accounts. …Kuznets’s measure of the nation’s total economic output came to be known as the gross domestic product, familiar today as the GDP. …Yet GDP faced criticism from the start, including from Kuznets himself. The welfare of a nation can “scarcely be inferred” simply from a measurement of national income, he stated in his first report to Congress on the subject.

Kuznets also recognized that not all economic growth is created equal. “Goals for ‘more’ growth should specify more growth of what and for what,” he would later write in The New Republic, also noting that, in dictatorships, growth was sometimes achieved through oppression or by goading people to work harder out of fear and hatred of foreign enemies. Kuznets wanted national ledgers to have both plus and minus columns, though the kinds of economic activity that went into each was open to debate. Kuznets himself thought that military spending should be subtracted from GDP, rather than added to it as it is today, because defense spending is something a nation is compelled to do by its potential attackers; the money could otherwise be used to improve citizens’ standard of living. Kuznets was no great fan of consumer culture. Echoing Adam Smith, who felt that some forms of economic activity were undesirable and destructive, Kuznets declared that GDP should reflect economic goals ”from the standpoint of a more enlightened social philosophy than that of an acquisitive society.” Among the activities that he felt should be red-inked as “disservice rather than service” were advertising and financial speculation. He wondered aloud whether the unpaid work of housewives was among the activities that should be included in national accounts. …

Kuznets was later echoed by Robert F. Kennedy in a speech he made just three months before his assassination in 1968 as he pursued the United States Presidency. Noting that material poverty in the US was matched by an even greater “poverty of satisfaction, purpose, and identity,” Kennedy decried GDP as a poor measure of the state of the nation. “Too much and for too long, we seemed to have surrendered personal excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things”, he said. The GDP was buoyed, he noted, by cigarette advertising, ambulances, home security, jails, the destruction of redwood forests, urban sprawl, napalm, nuclear warheads and the armored vehicles used by police against riots in American cities. “It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country. It measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile,” Kennedy said.

You and I can’t do much about national policy metrics, but we are in control of how we evaluate the health and welfare of our own lives. How much time do you spend developing and valuing your courage, wit, wisdom, devotion, or compassion?

To be honest I think I have much room to improve here, but to highlight a point MacKinnon makes in his book, our society makes it difficult and non-obvious to do so. Everything we see is steeped and saturated in a materialistic perspective, to the point that hearing a public official talk about devotion or integrity is (for me) a discordant experience.

That Kuznets at least on the record pondered whether or not domestic labor should be accounted for on the national ledgers almost a century ago is a reminder that it doesn’t have to be this way.

I highly recommend the book.

Speaking of books…

You can now buy a print version of my book, Deep Response, without having to deal with Amazon. Here’s a link to buy a print-on-demand copy via IngramSpark. If audiobooks are your jam, stay tuned, I should have that up and available sometime in February.

Personal Active Quests

ttm<=GEBR (trailing twelve month cost of living no more than the global equitable burn rate, which is ~$7,500/yr. Current cost of living: $12,652/yr.=

45min weighted Murph. (Current PR: 41min unweighted.)

Get a fatbike and acquire Alaska winter fatbiking skills (how not to freeze my toes off at -25F etc).

Scale back screen time. I’ve been experienced involuntary reactions of revulsion to anything close to adtech recently and a sort of yawning abyssal horror of the apparent acceleration of our culture towards enshittification. Purely for mental health reasons I’m taking steps to reduce my exposure to this (without going head-in-sand) and double down on the kinds of experiences I actually want to be having.

Recommended Reading

Nate Hagens podcast episode with Christian Sawyer about decentralized “un”inentional community building, work parties, and internal work. Inspiring.

Unraveling the Complexity of the Jevons Paradox: The Link Between Innovation, Efficiency, and Sustainability, by Giampietro et al. Related to understanding how greater efficiency is not the solution to all of our problems.

Quote

"One day you will wake up and there won’t be any more time to do the things you’ve always wanted. Do it now." Paulho Coelho